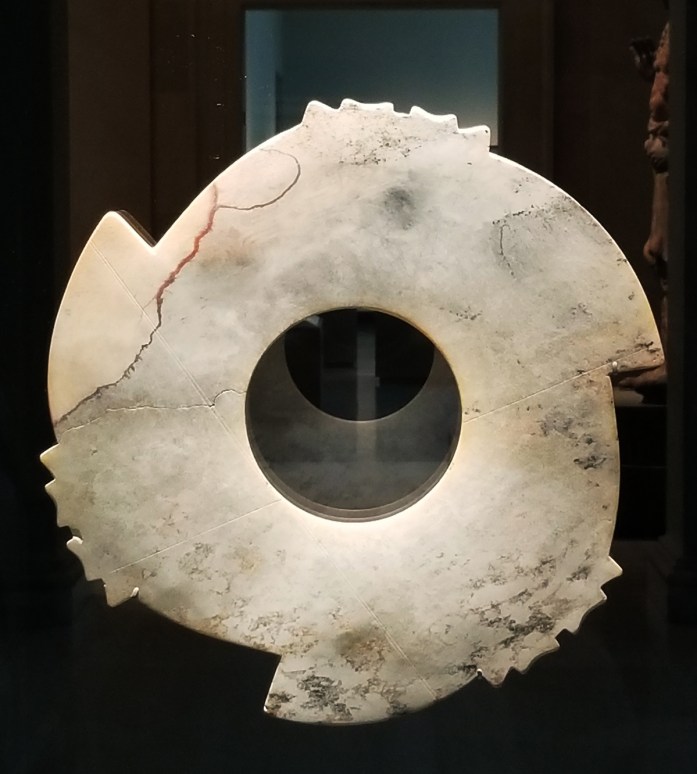

Notched disk, at the Freer Museum, Washington DC. China, probably Shandong province, late Neolithic period, 2500 BCE. The purpose of this intriguing object has never been established.

Not knowing, uncertainty, the pathless path, that which lives outside of language—these are themes that appear with determined insistence throughout the thousands of short essays I have posted here on Slow Muse. But rather than bringing me closer to the essence of these ideas through writing and through my studio practice, they have deepened in their mystery and essential incomprehensibility. The “don’t know mind” came into my life as a comforting Zen phrase. Over time it moved into the main house, and now it runs the joint.

Thank you to Ann Hamilton for her simple admonitions on this topic:

One doesn’t arrive—in words or in art—by necessarily knowing where one is going. In every work of art something appears that does not previously exist, and so, by default, you work from what you know to what you don’t know. You may set out for New York but you may find yourself as I did in Ohio. You may set out to make a sculpture and find that time is your material. You may pick up a paint brush and find that your making is not on canvas or wood but in relations between people. You may set out to walk across the room but getting to what is on the other side might take ten years. You have to be open to all possibilities and to all routes—circuitous or otherwise.

.

But not knowing, waiting and finding—though they may happen accidentally, aren’t accidents. They involve work and research. Not knowing isn’t ignorance. (Fear springs from ignorance.) Not knowing is a permissive and rigorous willingness to trust, leaving knowing in suspension, trusting in possibility without result, regarding as possible all manner of response. The responsibility of the artist…is the practice of recognizing.

Perhaps you too follow a daily ritual that invites your consciousness to step away from metrics, from the productivity-focused nature of our cultural moment. You may, like me and many of my closest cotravelers, center yourself daily in the essential practice of your art making that must, by definition, tap into something else altogether.

More from Hamilton:

A life of making isn’t a series of shows, or projects, or productions, or things: it is an everyday practice. It is a practice of questions more than answers, of waiting to find what you need more often than knowing what you need to do. Waiting, like listening and meandering, is best when it is an active and not a passive state.

So back into the inchoate I go. As many times as I have explored these concepts, I keep coming back to them in spite of feeling answerless. And my current discomfort with language can be seen as a good thing since that often is a reliable indicator of something else going on, TBD. And to that I say yes, yes, yes.

I love this “inchoate” region with its lack of answers, because it differs to greatly from the daily pragmatism of accomplishing one thing to get to another. Sometimes, a bit of stillness feels essential. That notched disk is AMAZING! What is it made of? How large is it? I’m full of questions (but I don’t have to have answers…)

Ann, it is quite large–maybe 30 inches? It is on display in the Freer Museum, in the rooms to the left if you enter from the Mall side. I was so taken by the space and the beauty of the object. So glad you got it too!

Oh I love this! And I want to get on the plane to Boston immediately!

Oh yes oh yes!!